The Hagia Sophia was created to appear ethereal and mystical, with windows inlaid along the bottom circumference of the dome and thin walls in between, built to make it appear as if the dome was suspended in air. The poetry of the building, with its mesmerizing marble and effusive light through mosaic windows meant to portray “movement” and fluidity, and the light meant to convey otherworldly holiness.[1] The building was meant to inspire awe in both plebeian and erudite audiences, with its grandiose size and scale. But one can imagine the commoner entering the Hagia Sophia and being humbled by the mythical, expansive vastness of the colossal dome that appears to be floating in the sky and to believe that this building is the work of God—to believe that the cathedral was a manifestation of God and his works.

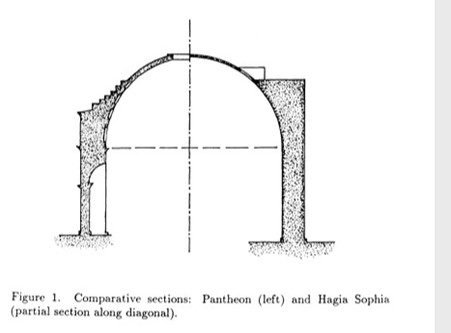

Historically, the building both references history and makes history: the Hagia Sophia had the largest interior space in

the world at the time and was among the first buildings to use a pendentive dome.[2] Built 1500 years ago, it’s meant not

only to represent God and his massive glory, but to illustrate the vastness of the Byzantine Empire. In creating the

Hagia Sophia, different materials from all geographical corners were imported to symbolize the hegemony of the Empire.

“Emperor Justinian wanted to create a structure that represented the entire Byzantine Empire, using materials from every

province to construct the basilica. The floor marble was produced in Anatolia, now eastern Turkey and Syria, and bricks for

the walls and parts of the floor came from North Africa.”[3] A comparison of the cross-sections of the Hagia Sophia “suggests

that Justinian’s builders were referring consciously to the Pantheon [temple] in their design.”[4]

The surroundings of the historical Hagia Sophia included grand palaces, baths, hospitals, universities, libraries, and law courts—of which all that remains are ruins. The historical context of the Hagia Sophia included the Great Palace and Hippodrome. Hagia Eirene, built by Constantine around 337, was the first cathedral of the city. Also found within close proximity to the Hagia Sophia are the Hospital of St. Sampson, Baths of Alexander, Theotokos Chalkoprateia, Trajan’s Forum, Senate House, Chalke Gate, Baths of Zeuxippus which once housed 80 statues; The Milion: tetrapylon adorned with statues of Fortuna; Basilica of Maxentius in Rome: Constantinople’s law courts, library, university, and Agora of Perge.[5]

The Hagia Sophia conforms to the traditional heritage of a basilica, and also of marble masonry building craft. The placements of the marbles are strategically mapped to create the greatest fluidity and to maximize reflection of light. Light appears through the many windows, especially those at the bottom circumference of the dome, to create a boundary of light between the inside and outside; thus effusing Nature, or the atmosphere, with the interior of the building.

The walls and columns express load bearing roles, and the dome pendentives are structural: “The Hagia Sophia has 104 columns, many made of marble, imported from the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus … and from Egypt”[6]; however the building is not truly tectonic, as the piers which hold most of the weight of the dome are embedded within the building’s walls, and “lead and lead sheets are used in the four main piers,” which carry most of the weight of the dome.[7] Nor is it expressionistic.

The programmatic nature of the Hagia Sophia is the worship of the monotheistic God; and which God is worshipped changes over history as different cultures and religions appropriate the ethereality and mysticism of the building to their specific religion. While the basilica began as a Greek Orthodox cathedral, it changed into a mosque, and then became secularized as a historical museum, then reverted back to a mosque when Recep Tayyip Erdogan, president of Turkey, appealed to populist Muslim sentiments.

The phenomenology of the building—how the building shapes your visual perception— gives the illusion of movement and creates an optical illusion of separation of the dome, since the light in between the pendentives illuminated by the many windows at the bottom circumference of the dome give the illusion of the dome floating. Symbolically, the building refers to nature, as the columns are like trees, the dome is the sky, the marble of the walls are like atmospheric waves, all of which are architectural elements that remind the viewer of a non-architectural idea: that is, nature and the sky and thus, celestial beings like God.

The typology, or the similarity in appearance, configuration and construction to previous buildings, is the Christian basilica and other archetypal Byzantine architecture. It “combined a traditional longitudinal basilican plan (a large rectangular hall having a high central space flanked by lower side aisles) with an immense central dome.”[8]

Overall, the Hagia Sophia refers to the Pantheon and other Greco-Roman architecture, but also creates history in its massive scale and size. It symbolizes ethereal holiness in light and fluidity and movement, symbolizing the Holy Spirit and its pervasive presence in the atmosphere. While it references the Pantheon, it differs in that it represents a monothetic religion wherein one God works with the State to proclaim its victory over other spirits and other states. While a religious monument, the Hagia Sophia is also emblematic of the power of Constantinople and Justinian forces ie, the state. It combines the materials of all provinces of the Byzantine empire to represent its hegemony.

[1] “Hagia Sophia and its Surroundings in Late Antiquity.” You Tube video, 4:02. April 25, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b5rLTfWpfq8

[2] Hagia Sophia Architecture Guide: A History of the Hagia Sophia, Master Class, Feb 25, 2022 https://www.masterclass.com/articles/hagia-sophia-architecture-guide#architectural-style-of-the-hagia-sophia

[3] “Building Materials of Hagia Sophia” https://hagiasophiaturkey.com/building-materials-hagia-sophia/

[4] Cakmak, A.S., Davidson, R., Mark, R. “Structural analysis of Hagia Sophia: a historical perspective” https://www.witpress.com/Secure/elibrary/papers/STR93/STR93003FU.pdf

[5] Khan academy

[6] “Hagia Sophia,” Wikipedia, March 18, 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hagia_Sophia

[7] https://www.masterclass.com/articles/hagia-sophia-architecture-guide#architectural-style-of-the-hagia-sophia

[8] Cakmak, A.S., Davidson, R., Mark, R. “Structural analysis of Hagia Sophia: a historical perspective” https://www.witpress.com/Secure/elibrary/papers/STR93/STR93003FU.pdf p 34