HARC E179 Understanding Architecture

3/10/2022

The Hagia Sophia, which means “Holy Wisdom,” is a 1500 year old monumental and massive cathedral in what is today Istanbul, Turkey. It was built as the crown jewel of the “imperial capital of Constantinople.”[1] As a Justinian work of architecture, its theme is one of movement and fluidity on the interior[2], and was the revolutionary in its “scale and ambition” and designed by two “theoreticians” well-versed in geometry, physics, and mathematics.[3]

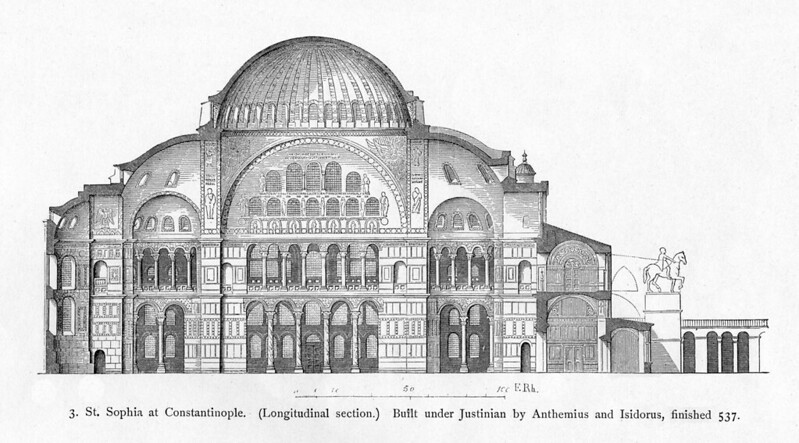

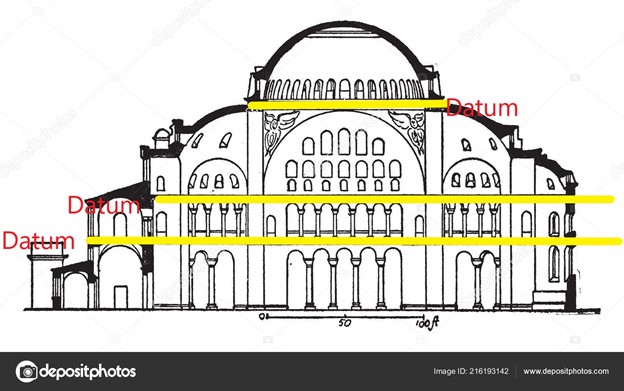

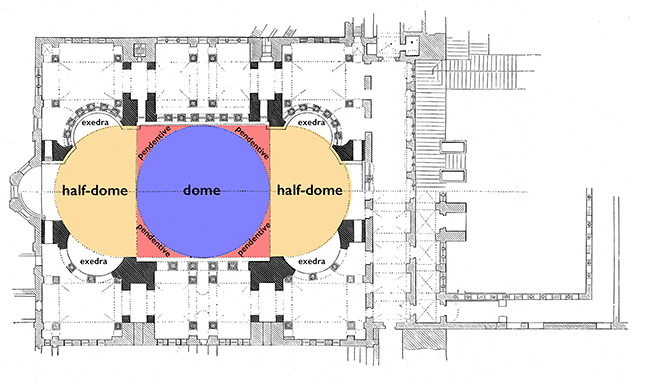

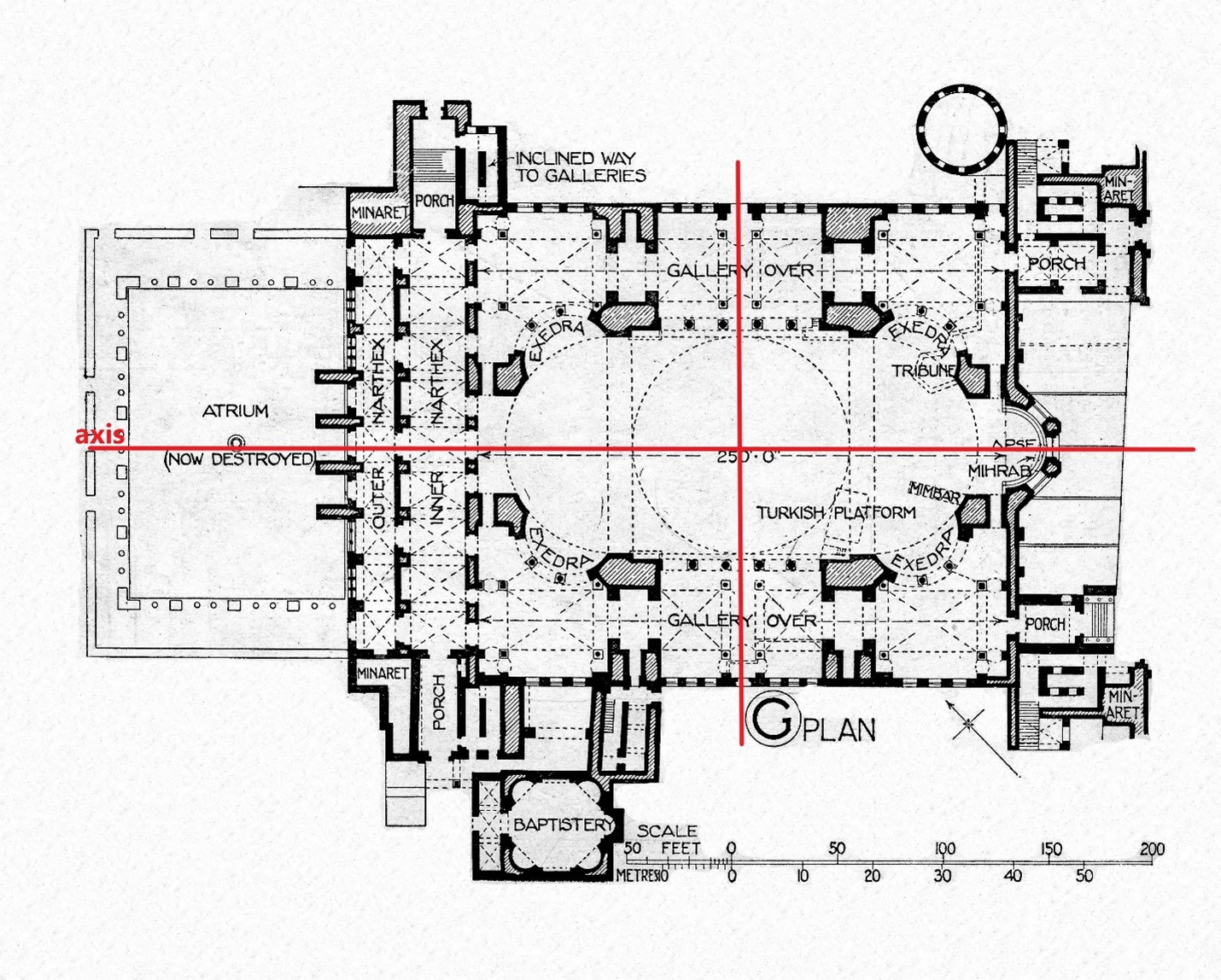

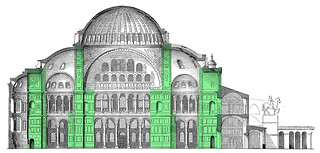

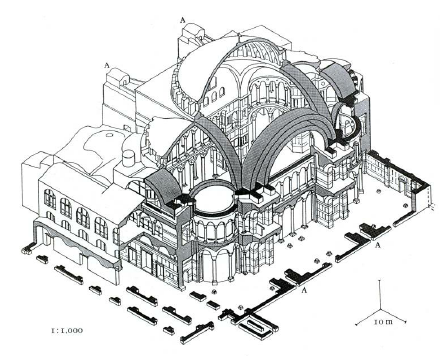

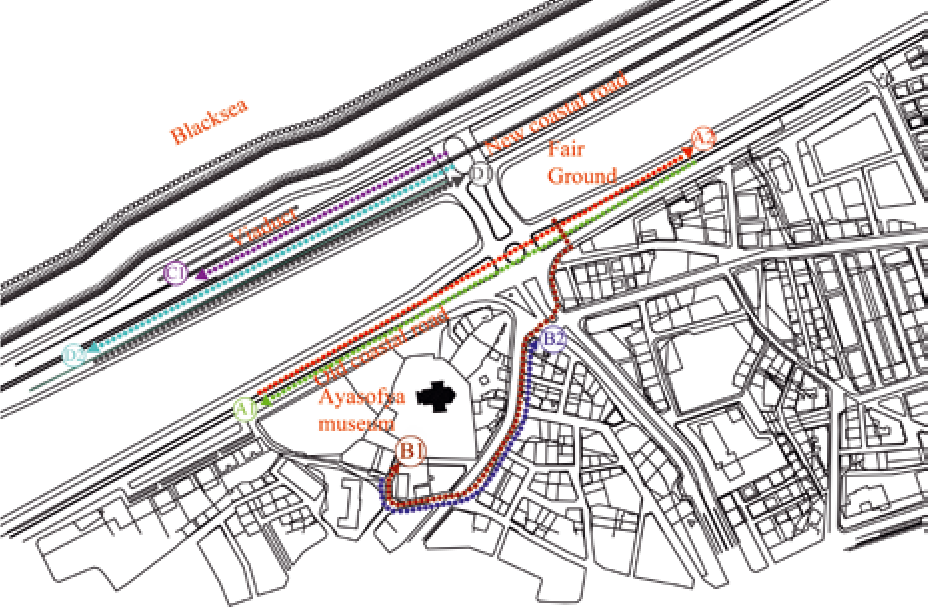

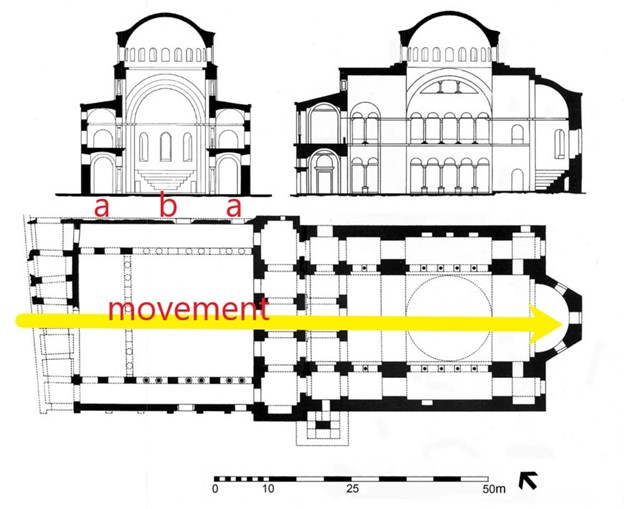

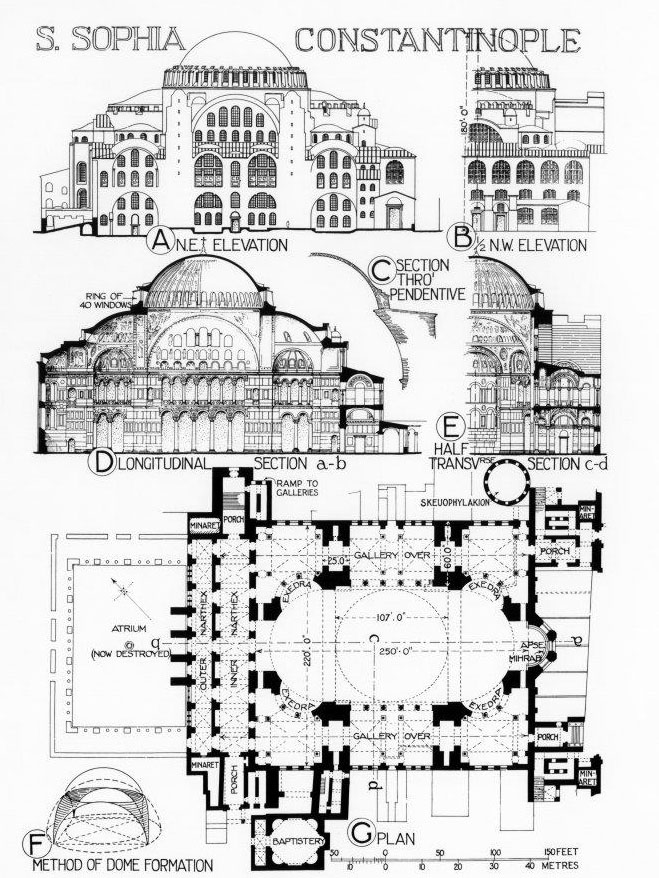

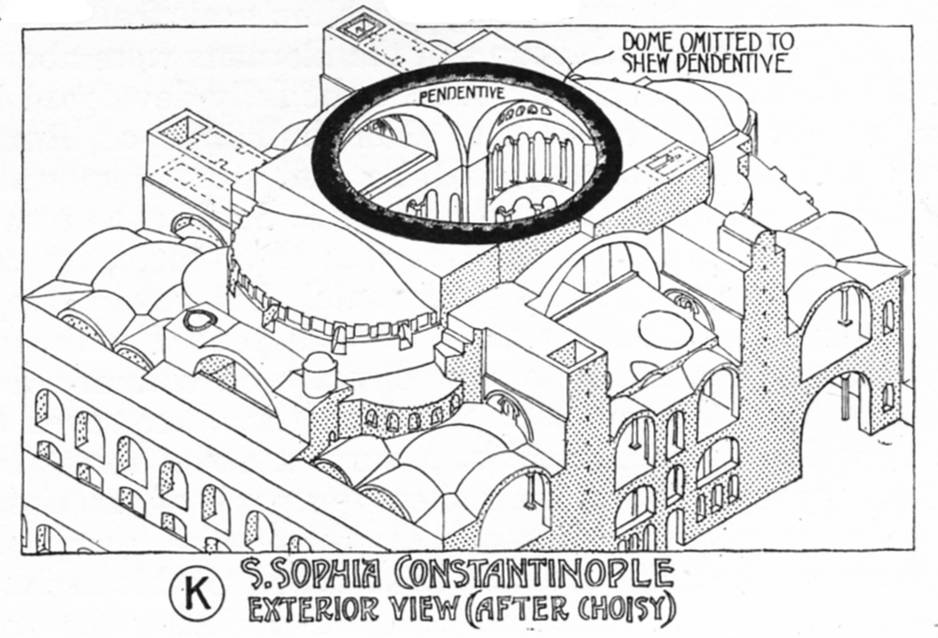

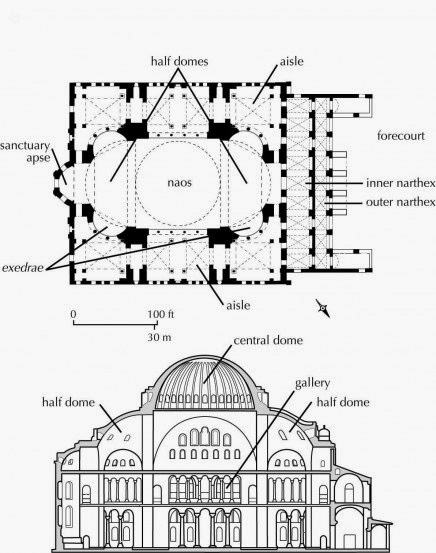

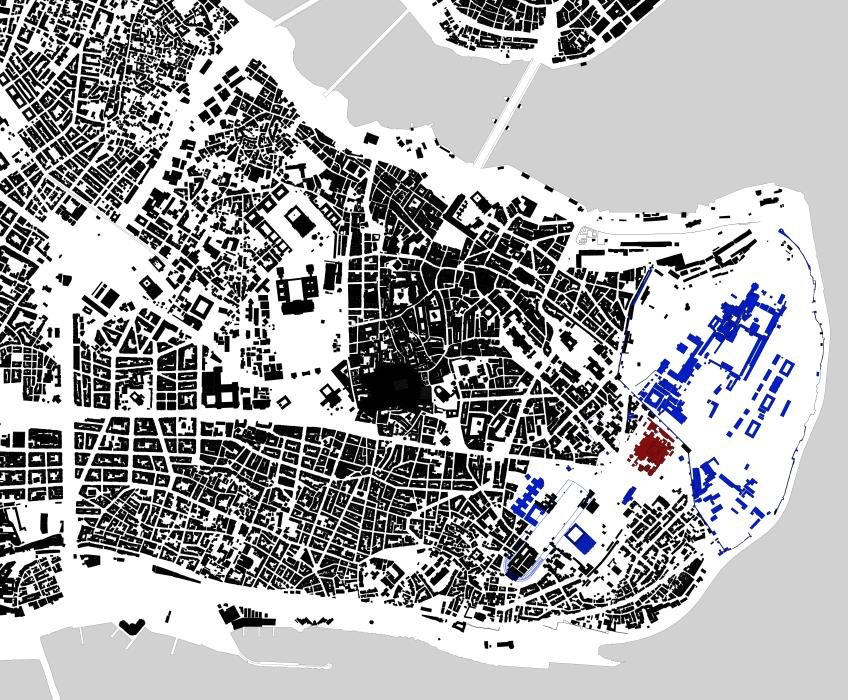

The Figure and Field of the Hagia Sophia: it is in a city and is situated in an urban landscape near the Black Sea (see Figure N). Thus, it is surrounded by trees and other buildings with the backdrop of the body of water. The datum of the Hagia Sophia runs in three different places, at the bottom of the top dome, at the bottom of the three smaller domes, and thirdly runs along the top of the bottom set of columns (see picture b). In regard to space, or the volume created by the built form, a “near square shape” is formed on the interior, with its ceilings shaped by a rounded dome, with two half domes on the ceilings of each side.[4] Francis Ching describes how “linear elements” “define transparent volumes of space”: “the four minaret towers define a special field from which the dome of Hagia Sophia rises in splendor.”[5] The massing of the building can be described by a square base, from which emerges “two half domes forming a rectangle of space.”[6] The Hagia Sophia’s massing an best be illustrated by four semi circles as the sides of a cube, with the diameter of each semicircle as the four bases of each side. Above that cube with the rounded sides is a dome, or half sphere, as depicted on slide 13 of Lecture 2 in Mark Johnson’s Understanding Architecture class.

The program of the Hagia Sophia has changed several times: it is now use as a mosque: it began as a Byzantine cathedral, which became a mosque, then a secularized museum, then reverted back to a mosque a couple years ago. The size of the Hagia Sophia (see picture m) is about “270 feet long and 240 feet wide,” and its “dome is 108 feet in diameter and its crown rises some 180 feet above the pavement”[7] In its scale the human is dwarfed and it feels as one is standing in a “canyon” (see picture m).[8] The structure of the building is constructed by “columns at the corner of each square.”[9] “[Anthemius] then filled the spaces between the arches with masonry to create curved triangular shapes called pendentives,” and the “pendentives and the tops of the arches combine to create a strong base for the dome.”[10] The enclosure of the building, that which separates the inside of the building from the outside, is solid wall with many windows, especially at the top of the building or bottom of the dome.

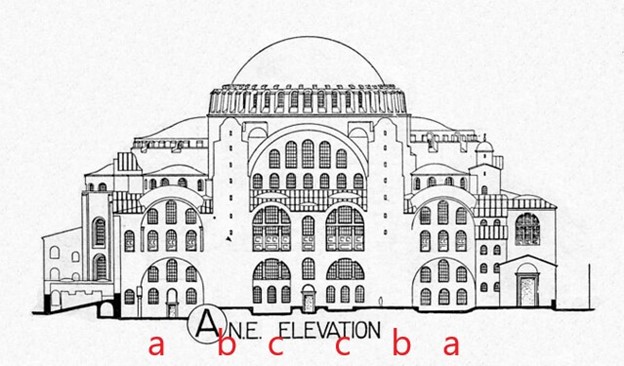

Rhythm (see picture e and i): from the North East side one can see a pattern of a, b, c, c, b, a. From the narrow side of the building one can see an a b a pattern with the half dome designated as the a’s and the main dome representing b. The proportion of the Hagia Sophia is mostly equilateral on all sides of the plan, however, the half domes of the building create a rectangular shape at its base. The height the building is approximately half of its width and length. The axis cuts across the center of the building as can be defined by the middle of the building that is a walkway to the apse (see picture d). The movement (see picture i) can be described as a procession from the entrance to the back of the building where ceremonies were held.

The view of the Hagia Sophia leads to surrounding buildings in Istanbul, as the windows are divided into many squares: the clear windows were once stained-glass windows of various colors but became clear over time. The material of the Hagia Sophia is built from marble imported from all areas of the Byzantine empire, since Justinian wanted the cathedral to represent the whole of the empire. The marble slabs are cut and opened up, revealing intricate and symmetrical shapes and patterns that signify movement.[11] The natural light pours in from the many windows of the buildings, most significantly from the forty windows that puncture the base of the dome, creating the illusion of a floating dome. Moreover, gold mosaics line the pendentives and the spaces between the windows, illuminating the dome even further and creating a effervescent, mystical ambiance. The exterior of the Hagia Sophia is light pink/ beige/ tan, and the interior marbles are various colors with gold mosaics. The decorations of the Hagia Sophia are limited to simple crosses and now Islamic calligraphy, but stray away from pictures of Jesus and Mary, since at the time, they did not want to create images of God as prohibited by the Bible.[12]

Bibliography

1. Ching, Francis. Architecture: Form, Space, and Order. Van Nostrand Reinhold Company. New York.

2. Cohen, Thomas. “Hagia Sophia.” World History Encyclopedia. November 19, 2015. March 10, 2022. https://www.worldhistory.org/Hagia_Sophia/#:~:text=The%20dimensions%20of%20the%20extant,were%20first%20completed%20in%20537

3. https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/early-europe-and-colonial-americas/medieval-europe-islamic-world/v/hagia-sophia-istanbul

4. “Hagia Sophia.” Wonders of the World Databank. PBS Online. March 10, 2022. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/buildingbig/wonder/structure/hagia_sophia.html.

5. “Hagia Sophia.” Wikipedia. March 2, 2022. March 10, 2022. Hagia Sophia – Wikipedia

6. Jarus, Owen. “Hagia Sophia: Facts, History, and Architecture. March 1, 2013. https://www.livescience.com/27574-hagia-sophia.html

[1] “Hagia Sophia,” Wikipedia, March 2, 2022, March 10, 2022, Hagia Sophia – Wikipedia.

[2] “Hagia Sophia,” Khan Academy, March 10, 2022, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/early-europe-and-colonial-americas/medieval-europe-islamic-world/v/hagia-sophia-istanbul

[3] “Hagia Sophia,” Khan Academy, March 10, 2022, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/early-europe-and-colonial-americas/medieval-europe-islamic-world/v/hagia-sophia-istanbul

[4] Cohen, Thomas. “Hagia Sophia,” World History Encyclopedia, November 19, 2015, March 10, 2022, https://www.worldhistory.org/Hagia_Sophia/#:~:text=The%20dimensions%20of%20the%20extant,were%20first%20completed%20in%20537.

[5] Ching, Francis, Architecture, Form, Space, and Order, Van Nostrand Reinhold Company, New York, Page 26

[6] “Hagia Sophia,” Khan Academy, March 10, 2022, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/early-europe-and-colonial-americas/medieval-europe-islamic-world/v/hagia-sophia-istanbul

[7] Jarus, Owen, “Hagia Sophia: Facts, History, and Architecture,” March 1, 2013, March 10, 2022, https://www.livescience.com/27574-hagia-sophia.html.

[8] “Hagia Sophia,” Khan Academy, March 10, 2022, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/early-europe-and-colonial-americas/medieval-europe-islamic-world/v/hagia-sophia-istanbul

[9] “Hagia Sophia,” Wonders of the World Databank, PBS Online, March 10, 2022, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/buildingbig/wonder/structure/hagia_sophia.html

[10] “Hagia Sophia,” Wonders of the World Databank, PBS Online, March 10, 2022, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/buildingbig/wonder/structure/hagia_sophia.html

[11] “Hagia Sophia,” Khan Academy, March 10, 2022, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/early-europe-and-colonial-americas/medieval-europe-islamic-world/v/hagia-sophia-istanbul

[12] “Hagia Sophia,” Khan Academy, March 10, 2022, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/early-europe-and-colonial-americas/medieval-europe-islamic-world/v/hagia-sophia-istanbul

click on pictures to see sources