Spring 2022 taught by Professor Mark R. Johnson

In 1939, by the time Wright was commissioned to design the museum, he was already a successful architect. In 1905 he had designed the construction of the Unity Temple in Oak Park, Illinois. It was renowned as a forerunner of modern architecture, with its use of reinforced concrete. Additionally, in 1935 Wright completed Fallingwater, which was a rural Pennsylvania house built over a waterfall. This building earned the title of National Historic Landmark. Although it took 15 years for the Guggenheim to be finished being built, it is generally known to be Wright’s most acclaimed masterpiece.[1]

History Behind the Guggenheim Museum

The museum is named after a mining tycoon who began collecting art after his retirement in the 1930s.[2] Solomon R. Guggenheim, philanthropist and art collector, acquired European and American abstract paintings and displayed them in a rented space which he called the Museum of Non-Objective Painting. Soon, however, the need for a permanent home for these artworks,[3] including works from Vasily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Marc Chagall,[4] became apparent. Museum director Hilla Rebay commissioned Wright.[5] Rebay was a “German baroness and artist.”[6] On June 1, 1943, Rebay’s letter to Wright requesting him to design a museum, which she aspired to be a “temple of spirit, a monument.” She said she wanted an architect who is a “fighter, a lover of space…an originator, a tester, a wise man.”[7]

Wright was the perfect man for the job. He believed in wisdom of geometry and the philosophy that form and function are intertwined. And he believed in the power of organically formulating the design of a space to reflect the nature of its surrounding; To Wright, “geometry had cosmic meaning and that its use as the means of ordering design connected man to the cosmos. In this idealistic and romantic view, architecture could provide a means of harmony between the individual, society, and the universe”

Wright’s affinity for geometry stems from his childhood: his mother aspired for her son to become a great architect, and gave him maple wood blocks as his play toys at a very young age. His fascination with the wood blocks in youth is reflected in his architectural designs

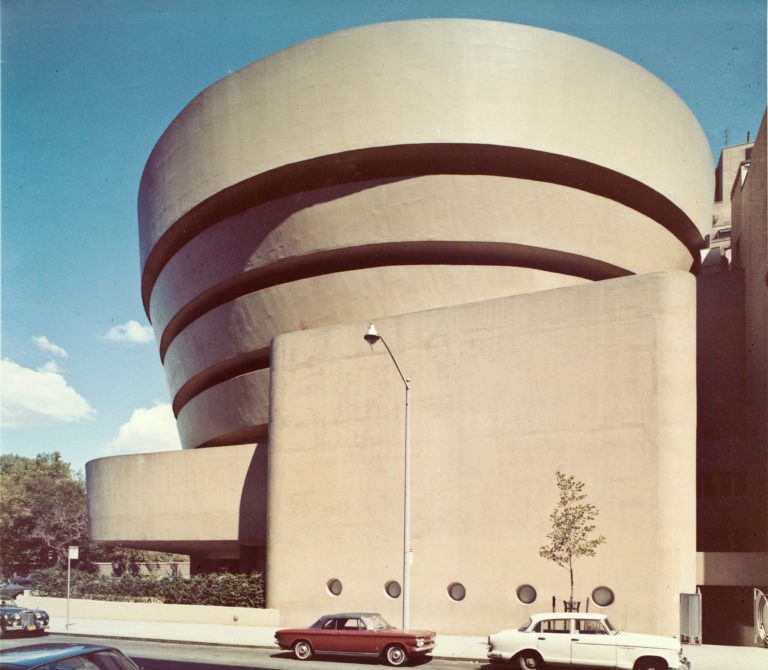

While most buildings are comprised of rectilinear spaces, Wright thought more organically, taking inspiration from the shapes found in nature. Literally thinking “outside the box,” Wright thought in curves, straight lines, geometric shapes, and organic shapes.[8] The organic colors of the Guggenheim contrasts starkly wih the” strict Manhattan city grid.”[9] To Wright, geometry contained within it symbolism: the circle represented infinity, “the triangle, structural unity; the spire, aspiration; the spiral, organic progress; and the square, integrity.” One can discover most of these forms in the Guggenheim Museum’s architecture.[10]

Just as Wright believed that form works in conjunction with function, unlike his predecessor who believed that form follows function, many believed that the museum achieved its original intent on creating a beautiful symphony between the artwork and the museum itself.[11]

Standing on the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum construction site in 1957, architect Frank Lloyd Write proclaimed, “It is all one thing, all an integral, not part upon part. This is the principle I’ve always worked toward.” The “principle” that Wright referred to is the design ideology that he developed over the course of his seventy-year career: organic architecture. At its core, the principle was an inspiration for spatial continuity, in which every element of a building would be conceived not as a discretely designed module, but as a constituent of the whole.[12]

The building itself has, like a living organism, evolved over time. Although its essence, the “overall integrity and character-defining spiral form” have not changed, the museum has grown and modernized via renovations as well as additions.

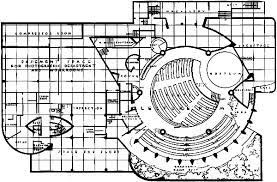

One can imagine the “grand ramp” and structure itself as a parking garage; but in fact, when the museum opened, “traffic literally drove through the building: entering on Fifth Avenue, continuing on a sweeping curved driveway, and exiting onto 89th street.” Wright was fascinated by cars and like Henry Ford, purported that automobiles represent democracy and freedom due to the “choice and control” that it imbues the individual. Although the early sketches include a driveway and parking spaces, they were substituted with an outdoor sculpture park; but the “driveway was fully functional until 1975”.

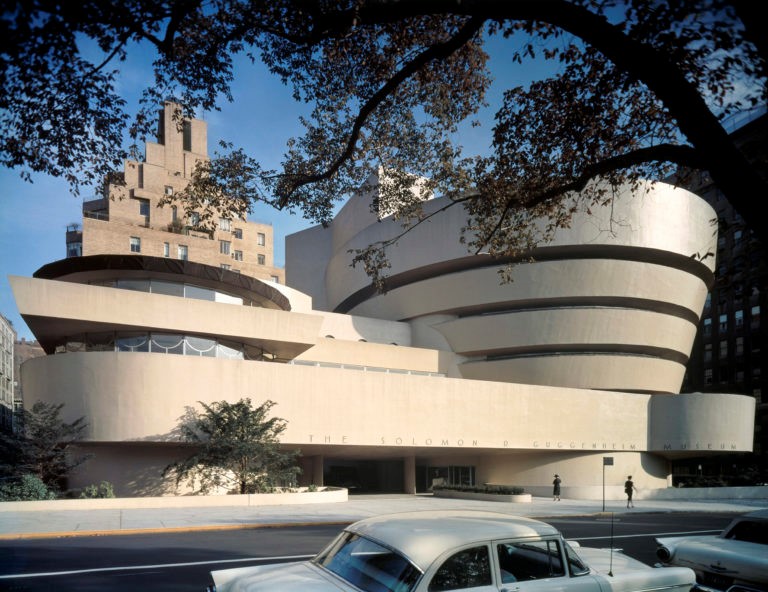

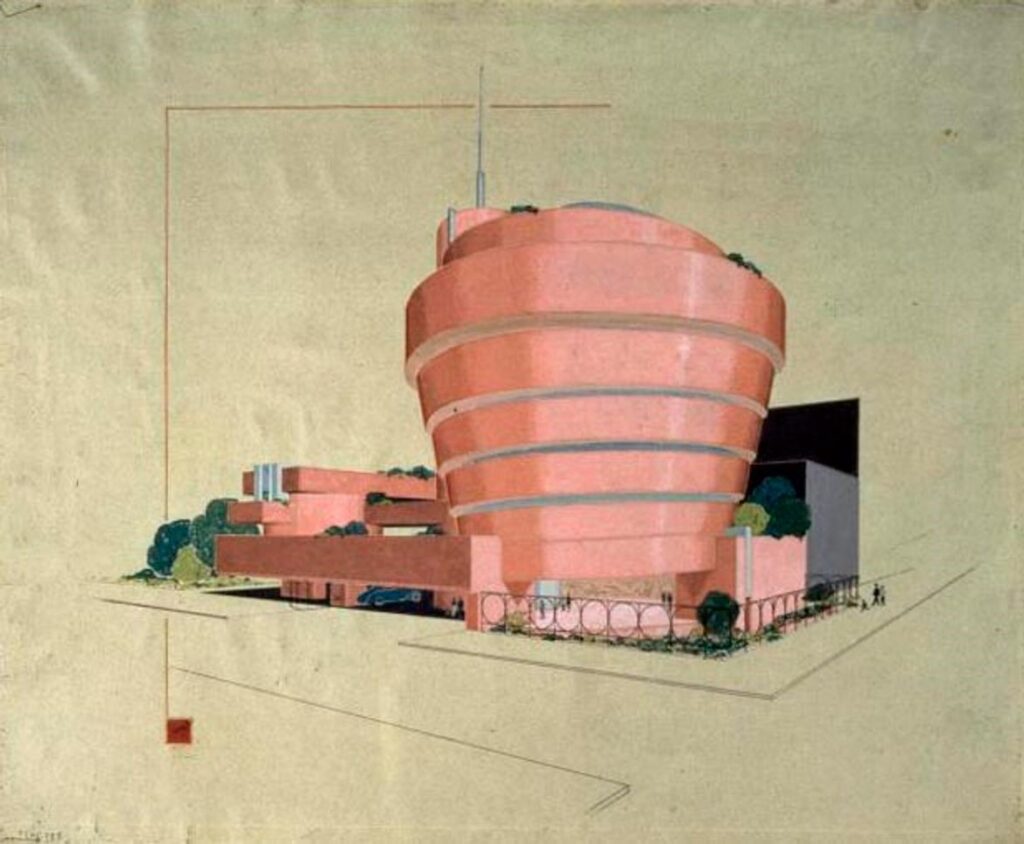

Even the exterior paint color has changed over time. Upon the Guggenheim’s grand opening, the exterior was a warm yellow-brown (see images F and G), which matched the interior of the terrazzo floors. This color matching gave the impression of the inside and outside being one continuous, smooth space. Wright wanted “every surface [to] be a consistent color. When James John Sweeney (the museum’s director from 1952-1960) insisted that the interior gallery walls be painted white, Wright wrote in protest to Harry Guggenheim, Solomon’s nephew” who was the president of the Guggenheim foundation.

He wrote:

This type of structure has no inside independent of the outside as one flows into and is of the other. Integrity is gone of these are separated and you have the conventional building of yesteryear. The features of this new structure are seen coming inside as well as the inside features going outside. This integration yields a nobility of quality and the strength of simplicity- a truth of which our culture has yet seen little and James has seen none. . . To thus tear the inside from the outside of the memorial would cheapen its character by actually destroying the virtue and beauty of the building

Wright did not win this battle, but he was able to choose the paint color of the exterior. After 5 years of the original paint color, the museum became a light grey that many seem to see as an off-white.[13]

There has been a model, “six sets of construction drawings” and 700 sketches that were created and revised which illuminate Wright’s design process over the span of the sixteen years he created the building.[14]

The Guggenheim is revolutionary for its time because it is the first museum that expresses itself as a work of art in and of itself. Many believed that it did the artwork a disservice by being so expressive. Was it overpowering the artwork? What about the slanted walls? Many artists wrote a petition expressing their distaste for their artwork to be displayed on a slanted wall. But overall, the museum achieves its purpose in integrating the beauty of both the art work with the architecture of the building. The effusive nature of the building can be expressed through the segments but open nature in between each display of artwork, which has been compared to the segments of a citrus fruit. Wright’s love for nature can be seen through the building: he detested that the building was to be built in New York City, but recognized that it would be a great addition to his portfolio of work. It being close to Central Square Park was enough for him.

Frank Lloyd Wright said, “form follows function- that has been misunderstood. Form and function should be one, joined in a spiritual union.” In his youth, Wright worked for Louis Sullivan (1856-1924) in his Chicago architecture firm. Sullivan was renown for his steel-frame constructions, which are often considered some of the first skyscrapers. Sullivan is known for his famous axiom “form follows function,” which became a overused saying in the whole of the design world, for example, in car design. Many architects followed this phrase, which means that “the purpose of a building should be the starting point for its design.”

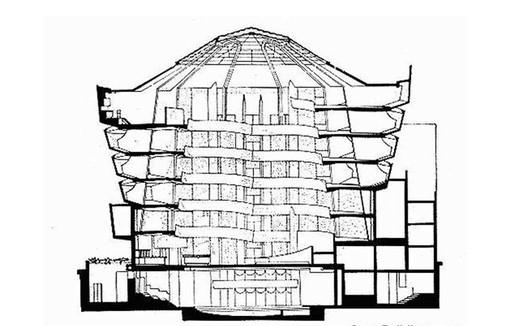

Wright built upon the teaching of his mentor by saying that “form and function are one.” This idea is apparent in the Guggenheim Museum. One can enter the building and climb up the ramp along the inside of the building, but Wright’s intention was for the visitors to enter the building, ride an elevator to the top, and relish in a continuous art-viewing experience while gradually descending along the spiral ramp.

Wright has said “it is hard…to understand a struggle for harmony and unity between the painting and the building. No, it is not to subjugate the painting to the building that I conceived this plan. On the contrary, it was to make the building and the painting a beautiful symphony as never exited in the world of Art before.”[15]

Frank Lloyd Wright said “I believe in God, only I spell it Nature.” Nature was first and foremost Wright’s biggest inspiration. “He advised students to “study nature, love nature, stay close to nature. It will never fail you.”” Wright’s love and appreciation started early in this life while working on his uncle’s farm in the summers. The rigorous farm work made a strong impression. From there he began to learn a sense of the deep mysteries of nature. People often interpret the Guggenheim Museum as a “nautilus shell” that “inspired the spiral ramp and that the radial symmetry of a spider web informed the design of the rotunda skylight”

Eric Lloyd Wright, who was Frank Lloyd Wright’s grandson, worked as his grandfather’s apprentice during the 1940s and 1950s, during the design of the Guggenheim. He remembers that “every Sunday at breakfast he’d give us a talk… And sometimes he would have placed before him a whole bunch of seashells. And he said, “Look here, fellows. This is what nature prodcues. These shells all are based on the same basic principles, but all of them are different, and they’re all created as a function of the interior use of that shell.”[16]

Organic brings to mind plants or animals, but for Wright the term organic meants something different. “For him organic architecture was an interpretation of nature’s principles manifested in buildings that were in harmony with the world around them. Wright held that a building should be a product of its place and its time, intimately connected to a particular moment and site—never the result of an imposed style.”

Wright was interested in context: the “relationship between buildings and their surrounding environments.” His belief that the building should “grow naturally” from the ground caused him to build buildings that complemented its environment. Additionally, he found a building should “function like a cohesive building, where each part of the design relates to the whole.” Wright’s organic architecture often includes elements found in nature, such as light, plants, and water. He often chose colors found in nature, such as brown and yellow, and red due to his study of Japanese culture. He chose to reveal the nature of the materials (tectonic), believed in opened spaces, and like to have a place for “natural foliage.”

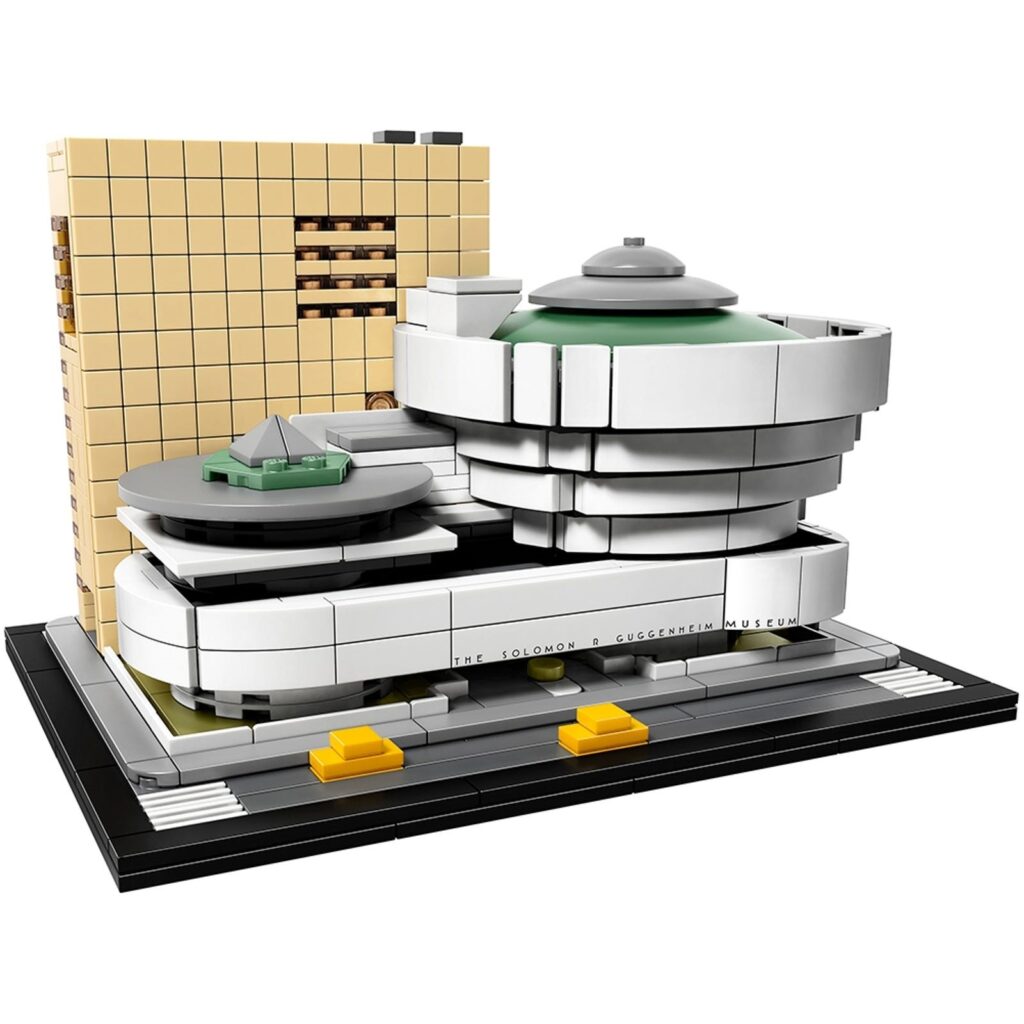

In the 1930s, Solomon R. Guggenheim’s first public exhibitions were held at the Plaza Hotel. In 1937, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation was created for the “promotion and encouragement and education in art and the enlightenment of the public.” “Solomon Guggenheim was the first president of the foundation, and Hilla Rebay [was] appointed its trustee and curator.” They acquired through donations or purchases about 600 artworks between 1937 and 1949. In 1939 the Museum of Non-Objective Painting opened in New York City. They rented abuilding at 24 East 54th St to show Solomon’s collection. In 1943 Frank Lloyd Wright was “commissioned to design a permanent museum.” In 1948-1949 the Solomon R. Guggenheim foundation acquired the Karl Nierendorf estate. In 1953, the construction of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum began. In 1959, the museum opened in New York City. In 1990 the restoration began, and reopened in 1992 after a “three-year restoration of its interior.” Simultaneously, the eight-story tower, which was designed by Gwathmey Siegle and Associates Architects, LLC” opened up. The foundational idea of the ten story tower came from Frank Lloyd Wright’s original plans, which did not come to fruition mostly due to financial reasons. This restoration opened up the “entire Wright building to the public for the first time, converting spaces that had been used for storage and offices into galleries. The restoration and expansion provides over 51,000 square feet of new and renovated gallery space, 1,400 square feet of new office space, a restored restaurant, and retrofitted support and storage spaces.”[17]

Analysis: What is it? What are its constituent elements? How are those elements ordered?

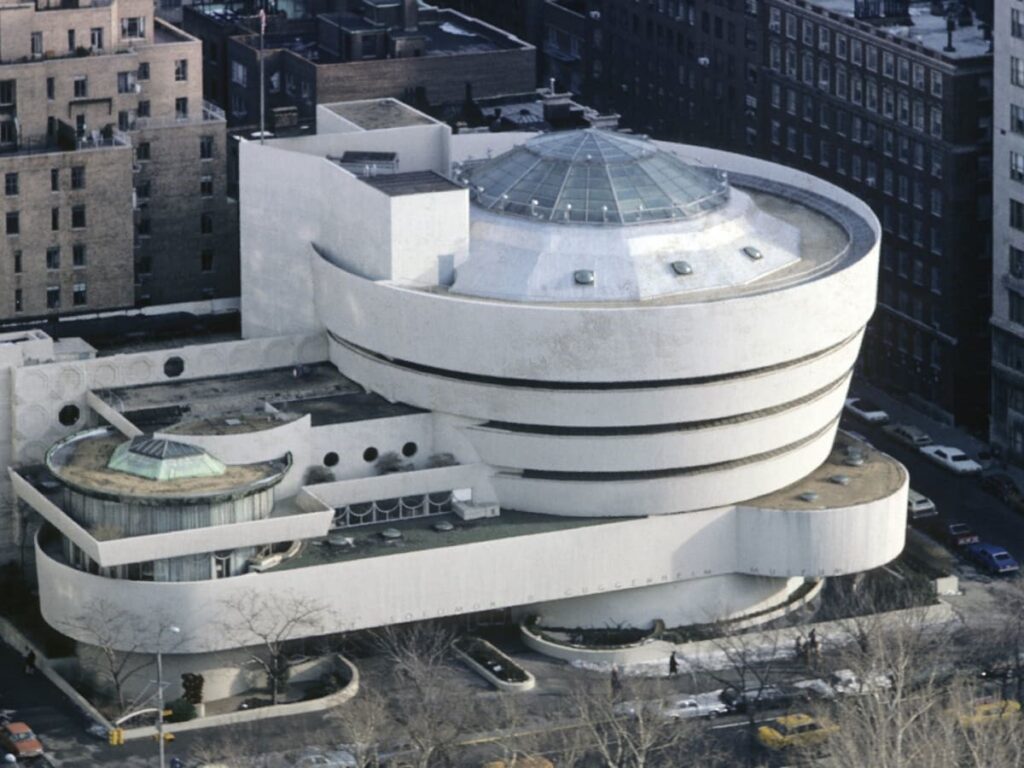

Figure and Field: the object and the background—The Guggenheim is a freestanding building in the sense that it does not match the architecture of its surrounding buildings. It is much shorter than the buildings in the area, which are rectilinear skyscrapers (see image J). Though not much shorter than its immediate neighbors, the buildings within the vicinity are much taller and narrower. It is at the edge of Central Square Park, so you can see a field of green, which appears to be a narrow strip of foliage lining a body of water (See image K).

The datum, unlike in other square or rectangular buildings cannot be described by horizontal or vertical lines. Instead the datum of the Guggenheim museum can be described by the spaces between each ribbon of concrete, which is a horizontal line at a tilt. The space is reminiscent of a “giant seashell, with each room opening fluidly into the next,”[18] “reflecting Wright’s love of nature.” Massing-the shape of building from outside: the building can be seen as a “a giant upside down cupcake.”[19] Its near cylindrical shape, gradually expanding its circled spirals upward can be compared to a “jellow mold.” Program: activities that take place in a building. More than 900,000 plus visitors visit the Guggenheim every year,[20] as it houses many sculptures, exhibitions, and contemporary art. It is an art museum.

Size: the ACTUAL dimensions relative to a human body. The space is “50,000 meters”[21]Scale: the PERCEIVED dimension relative to a human body: the building is 6 floors and is quite massive in size: the uniform color makes it seem larger in size since it is one cohesive whole piece. However the datum lines or the division between each floor is very distinct, scaling down the building to six floors each that makes the huge concrete mass more digestible and comparable to human scale.

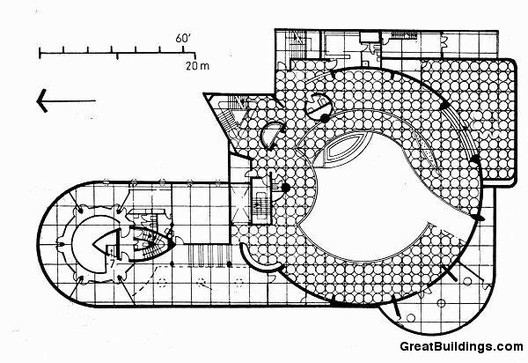

Structure: the way the building stands- “It took 7,000 cubic feet of concrete and 700 tons of structural steel to form the structure and shell of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Various subcontractors worked together to create the one-of-a-kind plywood forms that shaped the iconic sweeping curves of the building.”[22] Enclosure: the part of the building that separates inside from outside— the building is separated from the outside by concrete with only an oculus in the ceiling at the center of the cylindrical spiral. The rhythm can be described by A, A, A, A, A, A of the six repetitive layers of the building. The Proportion: the ratio of one dimension to another dimensions, is the repetition of form of one cylindrical circle that is maybe one fourth the size of the main part of the building, with a taller rectangular building additional building that is almost twice as high as the main building but much narrower.

The Axis is best described by drawing a line directly through the center of the main cylindrical building, with the two sides of the main cylinder folding in half of each other. The movement, or the experience of changing physical locations, is best described by first an entrance into an elevator that lifts a person up to the top floor, and a slow spiraling down the sides of the building until one reaches the bottom atrium. The view, or the composed vista created by the architecture, is the sky, through the oculus of the building which is composed of a spiderweb-like window. The material is stacked white cylindrical reinforced concrete. The light comes from the natural light of the oculus and the museum is brightly lit on the inside with artificial light to see the art work. The color of the building is light grey and terrazzo flooring in the interior. Decoration: surface ornamentation: the Guggenheim is completely devoid of any surface ornamentation, unlike the surrounding rectilinear buildings.

Synthesis: What is the architecture all about

What thinking ordered the design decisions?

What does the architecture express?

What does it mean?

Historic: building refer to other older buildings: the building is not historic at all, but is historic in the sense that it creates history. It is the first museum to be expressive and not a rectangular modest building whose main emphasis is displaying the art. In context, the Guggenheim is located on New York’s Museum Mile and does not refer to the buildings around it but does refer to the Central Park, in how organic and fluid the building is. The museum does not conform to a craft tradition but breaks tradition.

Nature: buildings refer to nature or break down boundary between inside and outside- the building creates a strong distinct separation from the outside except through the oculus. The Guggenheim is extremely sculptural, or expressionistic. The building is not tectonic: although it does not hide how it is built, it does not flashily display how it was built either. The programmatic nature of the building is the displaying of artworks. The Guggenheim is not phenomenological, as there are no shaping of ones visual perception. The building is not symbolic either, but many interpretations can be made of the building. In regards to typology, there is no similarity in appearance, configuration, or construction to previous buildings.

[1] Barnes, Sarah, “Frank Lloyd Write Brought His Masterpiece to Life In New York,” Home Architecture, My Modern Met, June 17, 2019, https://mymodernmet.com/guggenheim-museum-new-york-architecture/.

[2] History.com Editors, “Guggenheim Opens in New York City,” History, A&E Television Networks, November 24, 2009, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/guggenheim.

[3] Barnes, Sarah, “Frank Lloyd Write Brought His Masterpiece to Life In New York,” Home Architecture, My Modern Met, June 17, 2019, https://mymodernmet.com/guggenheim-museum-new-york-architecture/.

[4] History.com Editors, “Guggenheim Opens in New York City,” History, A&E Television Networks, November 24, 2009, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/guggenheim.

[5] Barnes, Sarah, “Frank Lloyd Write Brought His Masterpiece to Life In New York,” Home Architecture, My Modern Met, June 17, 2019, https://mymodernmet.com/guggenheim-museum-new-york-architecture/.

[6] History.com Editors, “Guggenheim Opens in New York City,” History, A&E Television Networks, November 24, 2009, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/guggenheim.

[7] Barnes, Sarah, “Frank Lloyd Write Brought His Masterpiece to Life In New York,” Home Architecture, My Modern Met, June 17, 2019, https://mymodernmet.com/guggenheim-museum-new-york-architecture/.

[8] “Geometric Shapes,” The Architecture of Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Guggenheim, May 2, 2022, https://www.guggenheim.org/teaching-materials/the-architecture-of-the-solomon-r-guggenheim-museum/geometric-shapes

[9] Perez, Adelyn, AD Classics: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum/ Frank Lloyd Wright, Architecture Daily, May 18, 2010, https://www.archdaily.com/60392/ad-classics-solomon-r-guggenheim-museum-frank-lloyd-wright.

[10] “Geometric Shapes,” The Architecture of Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Guggenheim, May 2, 2022, https://www.guggenheim.org/teaching-materials/the-architecture-of-the-solomon-r-guggenheim-museum/geometric-shapes

[11] History.com Editors, “Guggenheim Opens in New York City,” History, A&E Television Networks, November 24, 2009, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/guggenheim.

[12] Mendelsohn, Ashley, “Wright’s Living “Organism: The Evolution of the Guggeneim Museum,” Guggenheim, June 20, 2017, https://www.guggenheim.org/blogs/checklist/wrights-living-organism-the-evolution-of-the-guggenheim-museum

[13] Mendelsohn, Ashley, “Wright’s Living “Organism: The Evolution of the Guggeneim Museum,” Guggenheim, June 20, 2017, https://www.guggenheim.org/blogs/checklist/wrights-living-organism-the-evolution-of-the-guggenheim-museum

[14] Mendelsohn, Ashely, Illuminating Details from Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenhiem Blueprints,” https://www.guggenheim.org/blogs/checklist/illuminating-details-from-frank-lloyd-wrights-guggenheim-blueprints

[15] “Form Follows Function,” The Architecture of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, https://www.guggenheim.org/teaching-materials/the-architecture-of-the-solomon-r-guggenheim-museum/form-follows-function

[16]Frank Lloyd Wright and Nature, The Architecture of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, https://www.guggenheim.org/teaching-materials/the-architecture-of-the-solomon-r-guggenheim-museum/frank-lloyd-wright-and-nature

[17] Somon R. Guggenheim Foundation Timeline, https://www.guggenheim.org/history/foundation

[18] History.com Editors, “Guggenheim Opens in New York City,” History, A&E Television Networks, November 24, 2009, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/guggenheim.

[19] History.com Editors, “Guggenheim Opens in New York City,” History, A&E Television Networks, November 24, 2009, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/guggenheim.

[20] History.com Editors, “Guggenheim Opens in New York City,” History, A&E Television Networks, November 24, 2009, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/guggenheim.

[21] History.com Editors, “Guggenheim Opens in New York City,” History, A&E Television Networks, November 24, 2009, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/guggenheim.

[22] Chusid, Megan, How One Simple Materal Shaped Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim, https://www.guggenheim.org/blogs/checklist/how-one-simple-material-shaped-frank-lloyd-wrights-guggenheim

click on the picture to see the source